LLMs Aren't Tools

"The name is the thing, and the true name is the true thing. To speak the name is to control the thing." —Ursula K. Le Guin, The Rule of Names

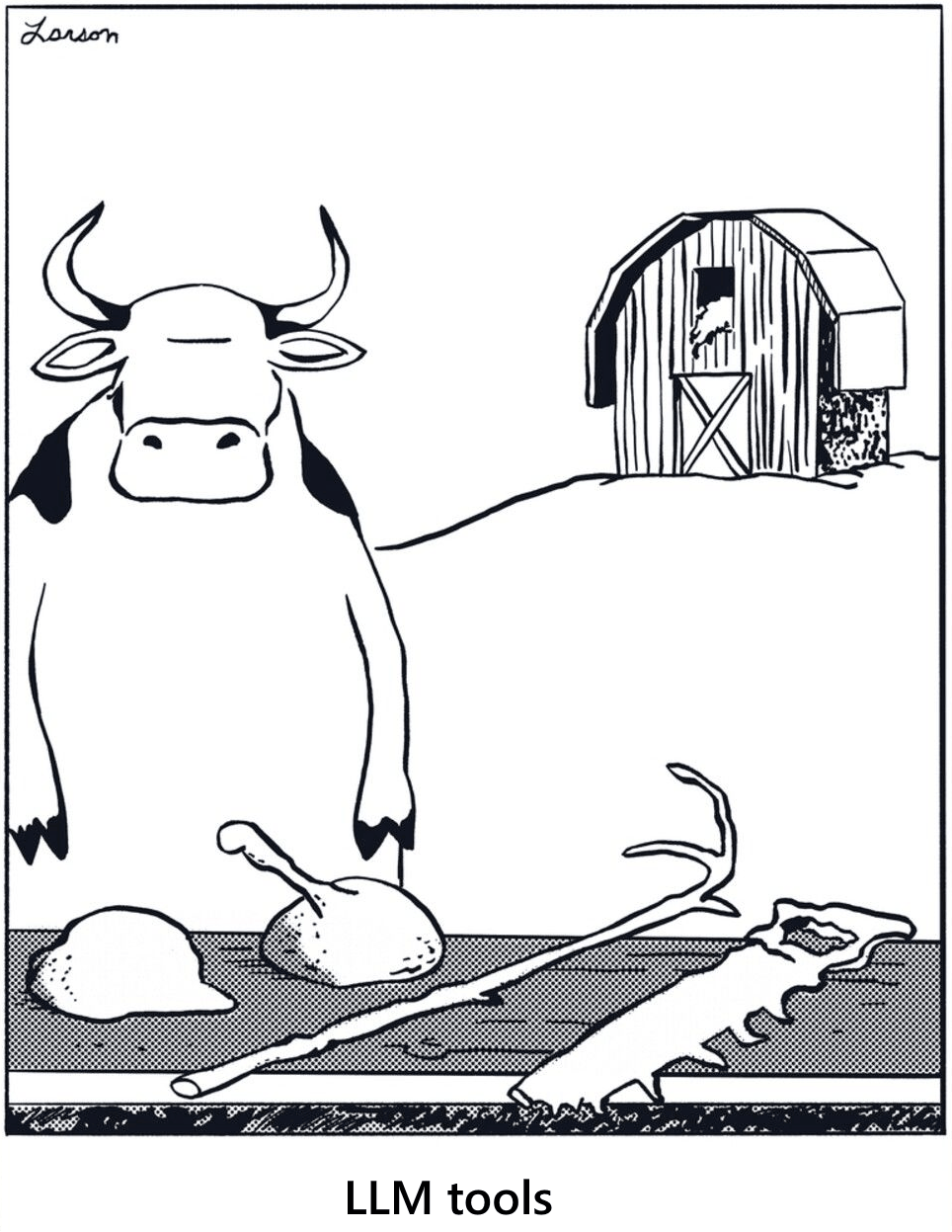

As software engineers, we refer to LLMs broadly as "tools". We think and talk about them as just another tool in our dev toolkit. This is reasonable, because it is how most of us started using LLMs, starting with Copilot. But as context windows have grown and models have become more capable and varied, this concept has grown stale and feels reductive. LLMs are no longer just tools. We use them from multiple interfaces (IDE/CLI/web/agentic) with different I/O expectations and workflow patterns.

There is value in taking a step back and thinking deeper about what is really going on when we interact with LLMs today. For example, these are some ways I use LLMs in my day-to-day:

- Turn this concept into code

- Explain this error

- Debug this code

- Find bugs in this code

- Code completion

- Show me where this lives in the codebase

- Answer this general question

- Optimize this code

- Write tests

- Restructure this code

- Simplify this code

- Create an implementation plan

- Create an architecture plan

- Convert this to a different language

- Make a graph of this flow

- Write documentation

This is hardly exhaustive. Most of these use cases have been added to my arsenal within the last year. Grouping these uses under a single "tool" label limits how I am able to differentiate these interactions and limits my imagination for how else I can benefit from LLMs.

LLMs as Multi-Tools

Let's consider each use case of an LLM as a separate tool. LLM as a code generator, LLM as a debugger, LLM as an architect, etc.

From this perspective, it is natural to think of LLMs as a multi-faceted tool with many uses, like a spreadsheet. This feels accurate because most software operates this way. We figure out what the software can do, and then we figure out the many ways we can use it.

LLMs are different, though. If I ask an LLM a question, I am using a much different tool than if I generate a Python function, ask for a summary or request an SVG of a pelican riding a bicycle. Each use case requires a different structure to the request, handles each request differently and produces differently structured results. The only consistent element is the text -> LLM -> text flow. We may always be passing text back and forth to an LLM, but that is just a high-level I/O detail, the same as grouping all woodworking tools together because they all "touch the wood."

A spreadsheet may have a similarly broad input (a 2D array of values), but the capabilities of a spreadsheet are the same whether I want to track inventory, build a graph or record sales. How I use a spreadsheet is defined by the functionality of the tool itself.

LLMs as Workshops

A more expressive metaphor is to think of the LLM as a workshop. We can send a broken chair to a workshop and expect a working chair to come back. We can send a diagram of a chair to the workshop and expect a chair to be built. We bring our expectations to the workshop and the workshop uses its knowledge (and our context) to produce what we want.

A workshop is different from a tool or collection of tools. It is a place where tools are used to achieve a goal. When you send a request to a workshop you cede control over many details, trusting that the workshop will figure out the best way to accomplish your task. As the person submitting a request you don't need to know every tool available in the workshop, and the workshop has more tools than you will ever know. But the more specific your request to the workshop, the more accurate the results will be.

This better parallels how engineers (and non-engineers) often think about their interactions with LLMs. If an LLM produces bad results we know that we can refine the context or add guardrails to improve our output. We also know that LLMs won't return a deterministic output, but the more we interact with them, the more we learn how to anticipate their output for a range of uses.

LLMs as a Consultants

As end users, we may understand that LLMs process prompts roughly work like this:

"LLMs process prompts by converting input text into numerical tokens, analyzing them through neural networks to understand context, and then generating responses by predicting the most probable next token one by one." - Google's AI Overview for "how LLMs process prompts"

It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that because we are inside a coding IDE or accessing the LLM from a CLI that we are interacting directly with the "token predictor" logic of an LLM. Recently someone ran an experiment on how LLMs react when given no intent within the prompt. The results are fascinating and expose how there is a lot more going on outside of a "token predictor" core.

Inference is a major element of LLMs, but it is easy to gloss over when troubleshooting our prompts since LLMs tend to handle inference quite well. If I consider my list of everyday use cases, LLMs handle many different types of requests and produce many different types of outputs. Each use case has different requirements for input/output expectations that I have sussed out for myself and internalized through usage.

This mirrors the challenge of trying to understand modern Google search results. Originally we had "PageRank Google," where search results were consistent no matter who was searching. Now we know results are highly customized by our search history, browser profile, location, etc. If I search for "python," I will get very different results than a non-programmer who is interested in snakes. If I am trying to understand how Google ranks search results I need to keep in mind that these ancillary factors affect the results I see.

We are used to internalizing "how the computer thinks" when programming. LLMs are already a black box to us, but adding this anticipation step further muddies our understanding—did my prompt fail because the context was incomplete, or was my intent poorly understood? Differentiating the cause may not always be clear but know that there are different factors at play can help in troubleshooting.

If we imagine the LLM as a workshop, I am never interacting with that workshop directly. I interact with something like a consultant who takes my vague request and reformats it into a more specific request that the workshop can fulfill. The consultant knows about me and my situation (my codebase) and uses that to adjust the request sent to the workshop. The consultant also knows all about the workshop (the LLM) and its capabilities, and how to get specific results from it.

This "consultant" perspective exposes how our prompts and LLM outputs are manipulated at a structural level. The "workshop" and "consultant" analogies focus on the user interface of LLMs when we interact with them manually through prompts. Hopefully, this gives some clarity on how it feels to interact with an LLM. The skills needed to communicate your intent with a workshop or consultant are much different from those used when writing code. Understanding that difference is necessary to develop strategies for improvement.

LLMs as Manufacturers

There is an entirely different way LLMs are used in production code. For example, we might already be an expert on making chairs and want to do more than bring individual requests to a workshop or consultant. In this situation we might want to channel our expertise into a blueprint for making an entire line of chairs, all adhering to our specifications. Each chair could be customized as long as they are within the boundaries of our design template.

This is using LLMs as a manufacturer. When interacting with a manufacturer, we no longer describe a specific chair but provide detailed schematics for making chairs in general. The manufacturer configures itself to produce chairs that fit our requirements. If our schematics are comprehensive we can have confidence that no matter what the user requests they will always receive a functioning chair.

With LLMs, we only ever have a single prompt to do everything. For each user request we must send our schematics along with the user request. The LLM will ensure the chair it produces adheres to the schematics while also trying to honor the user's prompt. This approach is common for many user-facing LLM products.

In code, this may result in one very large and detailed prompt or as a series of prompts connected by code. A narrowly focused product may work best with one prompt, but by differentiating requests early engineers can reduce an overweight context. For example, if I categorize a user's chair request as one of "recliner", "dining chair" or "stool", I greatly narrow the details I need to provide for each schematic.

LLMs as Applications

There is one more level of LLM usage that is possible as an end user but not often explored—treating the LLM as an application. We are familiar with the concept when we use Claude in "plan mode" or switch to "ask mode" or "debug mode" in Cursor. These are applications that create a loose structure around the LLM that frames any prompts we may pass.

What distinguishes an "application" from a "manufacturer" is a lack of rigidity. We are not treating the LLM as a DAG for running through if/else clauses or filling out an empty data structure. An application can be more precise than something like "debug mode" and can be thought of as a bespoke inference engine.

A project like Beads is a good example of an application. Where does the Beads application live? Looking through the code there are helper scripts and documentation with rules and a data store but the application itself doesn't exist. Each usage of Beads creates a meta-application in memory inside of the LLM as a process that is partially rebuilt to fulfill every request.

It is worth reflecting on how deeply weird and unexplored this behavior is. This is an LLM-native equivalent to "thinking like a computer." Engineers develop the ability to follow code logic as a muscle that unlocks deeper reasoning. Building up a similar muscle with LLMs is crucial if we want to develop applications that exist in this "meta" state.

Ok, Fine, LLMs Are Tools

I argue that LLMs are more than tools, but sometimes we use them as tools, like for code completion or summarization. We also use them as workshops, consultants, manufacturers and applications. These are metaphors, but each one implies a different set of expectations, both for what context we bring to an LLM and what we expect to receive from it.

Naming these differences gives us power to reason about which approach is best suited for different tasks. As our uses of LLMs expand so should our understanding and imagination about their capabilities and limitations.